Basketball, Semiology, and Pax Americana

Expansion, as the ‘Wisconsin school’ of American historiography has demonstrated, has been at the very core of the American experience. Empire constitutes the habitus—the dispositions that generate perceptions, practices and policies—of US elites. Imperial outlooks permeated the US as much as they did the European imperial societies where empire is a past that has never really or entirely passed. The United States emerged as a nation state in a global political economy of empires. Its expansion was conditioned by the overall expansion of the Euro-Atlantic imperial system. Notwithstanding American exceptionalist mythologies, expansion was founded on concepts of racial and cultural differences that were common to all the nineteenth-century empires. — Josh Howard

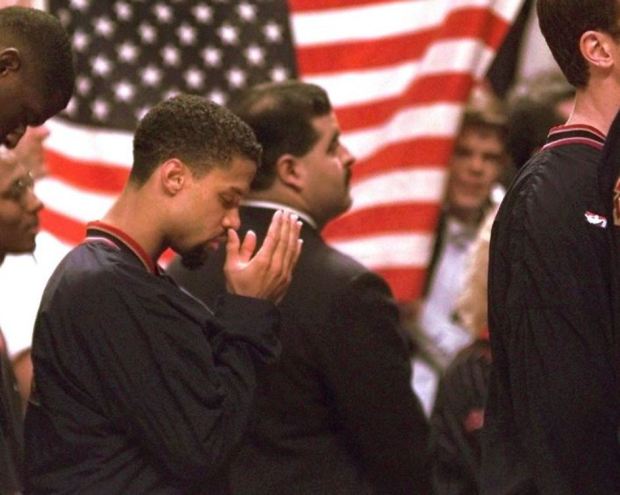

In 2008 a video surfaced in which Josh Howard, filmed during the performance of the American national anthem at Allen Iverson‘s “Celebrity Flag Football game,” looked into the camera and declared, “I don’t even celebrate that shit. I’m black.”

In the wake of Colin Kaepernick’s anthem protests, and in light of the various comparisons that have been drawn between him and other principled, politically aware athletes like Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf and Craig Hodges, I wanted to draw some attention to—and express appreciation for—Josh Howard’s less celebrated and more succinct critique of American patriotism.

While Howard did (eventually) apologise for his remarks, it wasn’t an especially convincing apology. Already a pariah in the eyes of fans and journalists due to his open marijuana use (which, as he has correctly pointed out, is his own choice and did not prevent him from doing his job), Howard probably understood that there would be no pleasing white America regardless of what he chose to say. Interestingly, during the same press conference at which he formally apologised for “disrespecting” the USA, Howard was asked what he thought about the prospect of playing alongside newly-acquired point guard Jason Kidd, a serial spousal abuser who would go on to drink-drive his car into a telephone pole in 2012 (behaviour apparently warranting back-to-back sportsmanship awards for “ethical behaviour” and “integrity”[1]).

Following his anthem scandal, Howard would play only one more full season of basketball in Dallas before injuries effectively derailed his career. This conveniently eliminated any need for the NBA to actively blackball him like it had Abdul-Rauf and Hodges (although Howard, a former All-Star and indisputably talented scorer, has apparently been attempting—unsuccessfully, so far—to make a comeback, so it’s quite possible that he is being frozen out after all).

Had he known how things would turn out, I’d like to believe that Howard, understanding that he had nothing to lose, would have stuck to his guns and refused to apologise. After all, what exactly was he apologising for? He hadn’t broken any rules or laws, and, moreover, he was expressing a view that is perfectly rational and correct.

With some notable exceptions, a great deal of the print and airtime devoted to Colin Kaepernick’s anthem protests has focused on form rather than substance. The pressing issues, according to establishment sports media, are whether white America is ready to have its beloved sports politicised, or whether Kaepernick’s kneeling will be sufficiently effective in ending racism. Missing from this narrative are, of course, the “bodies in the streets” that Kaepernick has cited as prompting his disobedience, and the fact that “[police] are being given paid leave for killing people.”

I don’t want to waste any time recounting what Kaepernick and other athletes are currently doing (I’ll assume that if you’re reading this you’re familiar with the situation). Nor am I going to belabour the point that Kaepernick is, of course, completely right about police brutality. Not only are racist cops all over America regularly rewarded for shooting innocent black people with impunity, they are punished if they don’t!

Colin Kaepernick has done a tremendous job drawing renewed attention to one of the most serious problems plaguing American society, and has at the same time made white conservatives deservedly uncomfortable. He has sparked a public debate, and I intend to contribute to that debate. The focus of my (constructive and well-meaning) critique of Kaepernick’s position will concern not police brutality but the brutality routinely inflicted on civilians all over the world by the military forces of the American Empire.

Following the discovery of his initially discreet and unremarkable protest (Kaepernick began by sitting down during anthem performances and only started kneeling to appease the belligerent turbo-patriots who control the NFL and American sports media), Kaepernick was grilled by journalists on the specific meaning of his disobedience. Predictably, he was asked what he thought about the American military, and, regrettably, he capitulated immediately: “I have great respect for the men and women that have fought for this country. […]. And they fight for freedom, they fight for the people, they fight for liberty and justice, for everyone.”

While some have argued, understandably, that it was something of a non-sequitur to request that Kaepernick issue a statement outlining his position on the military, it was—unintentionally, I’m sure—a salient question. First, it demonstrates a recognition that one cannot condemn American police for killing innocent people without also condemning the American military for perpetrating worse crimes on a far, far larger scale. Second, it inadvertently reveals the true and precise meaning of the American flag and national anthem: empire.

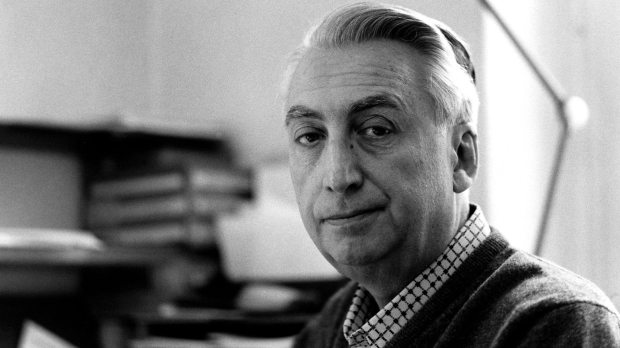

The development of publicity, of a national press, of radio, of illustrated news, not to speak of the survival of a myriad rites of communication which rule social appearances makes the development of a semiological science more urgent than ever. In a single day, how many really non-signifying fields do we cross? Very few, sometimes none. Here I am, before the field; it is true that it bears no message. But on the bleachers, what material for semiology! Flags, slogans, signals, sign-boards, clothes, suntan even, which are so many messages to me. — Roland Barthes

According to Roland Barthes, a sign (in this case The Star-Spangled Banner) is composed of both signifier (particular lyrics sung to a particular tune) and signified (military adventurism, white supremacy, capitalism). Likewise, the sign that is the American flag is composed of signifier (a piece of cloth) and signified (military adventurism, white supremacy, capitalism). We know that this is what the flag and anthem signify because these are the things that the American public scrambled to defend. Nobody accused Colin Kaepernick of disrespecting jazz, breakdancing, or Tom Waits, because the American national anthem does not signify these things. Rather, it signifies the overthrowing of democratically elected leaders and the installation of dictators; it signifies the plundering of resources; it signifies slavery; it signifies genocide. That an assortment of bellowing white men leapt to defend the American war machine in the wake of Kaepernick’s anthem protests tells you all you need to know about what it means to be an American patriot.

The Star-Spangled Banner doesn’t just signify racism in the semiological sense; the lyrics themselves are overtly racist! What I’ve outlined above isn’t just what America represents in some abstract sense—it is what the American ruling class has undertaken every single day for centuries. America’s empire surpasses all previous empires in its cruelty and destructiveness. If territorial expansion and the “removal” of indigenous populations falls within the settler colonial norm, the institutionalisation of domestic despotism is, according to Philip S. Golub, a singularity of the liberal American state: while the European imperial states exported their violence and subjugated peoples overseas, the United States applied despotism within large areas of its constantly expanding sphere of continental sovereignty. Slavery is one of the major distinguishing features of the early American empire.

We needn’t spend long dwelling on specific instances from America’s endless list of sins—this is a basketball blog, after all—but the following two examples are representative of America’s despotism at home and abroad. Speaking about the Native American population in 1868, beloved American war hero General William Tecumseh Sherman remarked: “we must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux, even to their extermination, men, women and children.” Two years later, Sherman, evidently in a lighter mood, wrote, “the more we can kill this year, the less will have to be killed the next war, for the more I see of these Indians the more convinced I am that they all have to be killed or maintained as a species of pauper. Their attempts at civilization are simply ridiculous.” In the twenty years that followed, the US army waged—in the words of General Philip Sheridan—a “campaign of annihilation, obliteration and complete destruction” against Native Americans.

Not content with spreading freedom and democracy at home, the United States’ military applied itself abroad in the same spirit. Senator Alfred Beveridge considered the conquest and subjugation of the Philippines (1899–1902) a necessary step to “establish the supremacy of the American republic throughout the East till the end of time.” Admonishing those of his peers who recoiled at the atrocities being committed by American forces in the archipelago, he advocated the extermination of all nationalist Filipino insurgents: “The Philippines are ours forever. […]. A lasting peace can be secured only by overwhelming forces in ceaseless action until universal and absolutely final defeat is inflicted on the enemy. To halt before every guerrilla band opposing us is dispersed or exterminated will prolong hostilities and leave alive the seeds of perpetual insurrection.”

But all of this is old news, ancient history. From the early 1950s until today, the United States has either been at war, supporting war-making, or sustaining predatory states almost constantly in one or another part of the empire: the Philippines, 1948–1954; Iran, 1953; Guatemala, 1954; Indonesia, 1955–1975; Congo/Zaire, 1960–1965; Cuba, 1961; Brazil, 1960s; Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, 1963–1975; Chile, 1973; Angola, 1975–1992; Nicaragua, 1980s; Grenada, 1983; Panama, 1989–1990; Afghanistan, 1980–1988; Iran–Iraq war, 1980–1988; Iraq, 1990–1991; and so on and so on. The notion that following the conclusion—by gratuitous nuclear genocide—of the Second World War, a period of peace, a Pax Americana, has spread across the globe, is an utter fantasy.

The vast and informal sphere of American Empire has always rested on a planetary security structure established during the Second World War whose forward points, the archipelago of land-based and floating military platforms disseminated throughout the world, constitute the mobile frontiers of American sovereignty. These platforms can and should be understood as the territorialised nodes of empire. The potential and often actualised violence of the security structure secures the wider informal sphere and allows the US, in the worlds of former Pentagon official Alberto Coll, to “move the international order in a favourable direction.” — Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf

The American ruling class still conceives of the United States as an empire, and their actions reflect this. America has polluted the world with military bases which, once established as “lily-pads” (what a pleasant euphemism!), grow aggressively, like tumours. The inherently expansionist character of America’s self-perpetuating military-industrial establishment requires, in the words of sociologist C. Wright Mills, “war or a high state of war preparedness” and a state of “emergency without foreseeable end.”

By the end of the 1990s, journalists (stenographers) and academics (propagandists) routinely compared the United Sates to “the greatest empires of the past,” and influential forces began dreaming of a new “American Century” along with a renewed and much expanded “American Peace.” In 1998, soon after an American bombing raid on Iraq, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright asserted: “If we have to use force, it is because we are America. We are the indispensable nation. We stand tall. We see further into the future.” In a particularly telling act soon after the George W. Bush administration was sworn in, the Office of the Secretary of Defense commissioned a still classified comparative study of ancient and modern empires to ascertain how they had “maintained their dominance.”

America’s commitment to permanent strategic supremacy cannot be considered a response to September 11. It was articulated in the early 1990s and is a state-centric approach that has nothing whatsoever to do with any presumed threat from transnational terrorism. No large-scale mobilisation was required to deter or destroy so-called “rogue states.” For that, pre-existing military capabilities were, as Afghanistan and Iraq proved, largely sufficient. Rather, America’s military adventures are invariably undertaken to further the economic interests of its ruling class. As Dick Chaney explained while testifying to the Senate Armed Services Committee in February 1991: “In addition to southwest Asia, we have important interests in Europe, Asia, the Pacific, and Central and Latin America. In each of these regions there are opportunities and potential future threats to our interests. We must configure our policies and our forces to effectively deter, or quickly defeat, such future regional threats.”

War is just a racket. It is conducted for the benefit of the very few at the expense of the masses. I served two years with the Navy, and during that period I spent most of my time being a high-class muscle-man for Big Business, for Wall Street, and for the Bankers. In short, I was a racketeer, a gangster for capitalism. — David Robinson

The problems that Colin Kaepernick identifies regarding the US military—that veterans returning from war don’t receive adequate support or treatment for mental health issues, and that the actions of racist police dishonour their “sacrifices”—barely scratch the surface. The military and the police exhibit many of the same problems in America: both are thoroughly corrupt institutions whose criminal behaviour and attempted cover-ups have been exposed for all to see. Both put guns in the hands of aggressive young men without providing them with adequate training or education, and both are utterly opaque and accountable to no one.

When questioned about his protest, Kaepernick cited “bodies in the streets” and cops “getting away with murder,” yet he doesn’t acknowledge the fact that these complaints can—and should—be levelled at the American military as well. Civilians all over the world are brutalised, raped, and killed by US military personnel daily. The ever-increasing militarisation of American police has simply given US citizens a taste of what people outside America have experienced for decades. Kaepernick must interrogate why he has “respect” for this institution, and why anybody who disrespects it is excommunicated.

I have great respect for the men and women that have fought for this country. […]. And they fight for freedom, they fight for the people, they fight for liberty and justice, for everyone.

Police are slave catchers; soldiers are gangsters for capitalism; Colin Kaepernick is Yanis Varoufakis. A popular and charismatic pseudo-Marxist career politician, Varoufakis continues to promote a bizarre and incoherent critique of the EU that both acknowledges the impossibility of democratising it while at the same time proposing to democratise it. Varoufakis will no doubt enjoy a long and lucrative career giving TED talks to imbecile Guardian readers, perhaps even making his way back into mainstream politics, but his self-serving Democracy in Europe Movement 2025 is a pointless red herring that will serve only to waste everybody’s time and energy. Similarly, Kaepernick, in maintaining that the United States can live up to its own myth without ending imperialism, presents a critique of American patriotism that is of severely limited scope.

Despite his shortcomings, Colin Kaepernick has shown infinitely more courage than the soft and obsequious Stephen Curry, who refuses to protest the anthem at all despite his coach’s blessing, and who has publicly endorsed Hillary Clinton, the candidate of Silicon Valley. But when discussing or celebrating the various anthem protests that have followed Kaepernick’s, it is crucial to acknowledge not just the informal backlash of marginal racist sports fans, but the official backlash of the various sports leagues themselves. The NBA has so far successfully conspired to prevent any kind of salient political statement from reaching its audience, replacing real protest with cowardly and depoliticised gestures that mean absolutely nothing.

Sevyn Streeter, for example, was told at the last minute that she would not be permitted to perform the national anthem on opening night in Philadelphia simply because she’d decided to wear a shirt that displayed the words “we matter.” Streeter later explained, “I…felt it was important to express the ongoing challenges and ongoing injustice we face as a black community within the United States of America—that’s very important to me. Yes, we live in the greatest country in the world, but there are issues that we cannot ignore.”

Yes, we live in the greatest country in the world.

The USA is a backward and oppressive country where to publicly assert that black people matter is obscene and forbidden. It is not great, or good, or even average. Streeter isn’t alone in citing this peculiar fantasy about American greatness in the face of indisputable evidence to the contrary. Even the more thoughtful responses to Colin Kaepernick’s protests have framed him as some sort of true American patriot bravely representing the real values that America stands for. But this is just more of the same delusional American exceptionalism that underpins the arguments of Kaepernick’s racist and conservative critics. To pat the American public on the back and assure them that Colin Kaepernick is fighting the good fight like a real American hero is to elide the reality of its brutal crimes against humanity, and unwittingly kills any serious and constructive discourse.

America is not a land of freedom-dispensing soldier-heroes who work tirelessly to promote democracy throughout the world; nor is it a bastion of free expression and progressive ideas. Rather than fighting over ownership of a phantasmagorical America that never actually existed, those prepared to challenge American empire must abandon any notion of patriotism and understand that to be labelled “un-American” or a “traitor” is a great honour.

The NBA, which likes to portray itself as a relatively progressive sports league, will do all it can to squash dissent and wring any political content from its players’ anthem-related demonstrations. To anybody anticipating a fresh wave of protests now that the NBA season is underway, understand that the NBA is not your friend; Adam Silver is a cold-blooded reptilian plutocrat whose words are emptier than the Smoothie King Center.

Radical NBA players need to take their cues not from acquiescent American football players, or from false prophets like Stephen Curry, but from real human beings like Josh Howard—people who say what’s in their heart and speak uncompromisingly. A protest isn’t really a protest if it’s sanctioned by the NBA. If your team tells you that you’re not allowed to wear a shirt with a particular slogan, wear it anyway. If your team tells you they don’t want you to sit during the national anthem, set the American flag on fire and boycott the league.

Until next time, death to America.

[1] I’m aware that the award is for “ethical behaviour” and “integrity” on the basketball court, but NBA teams each select one player from their roster to be considered for the award. Why even nominate Jason Kidd for an award like this? Were the rest of the Mavs and Knicks so unsportsmanlike? Are we really to believe that Jason Kidd, while he may regularly beat his wife and endanger people’s lives by driving drunk, is in all other respects a really nice guy? It is evident that the NBA conducts damage-control for its stars, provided they’ve only committed a mild transgression like abusing their wife for years on end, and nothing serious like sitting down.